Deciphering Constructivism in Cyndy’s Paintings

Curious about the history and meaning behind the geometric forms in Cyndy’s paintings, such as Aspect of Light?

Read Dr. Amelia Miholca ‘s article below about how Cyndy’s use of geometry relates to the early 20th century art movement Constructivism, a movement that heralded abstraction in art and changed forever what artists could paint.

Dr. Miholca received her PhD degree in Art History from Arizona State University. Her research examines constructivist and cubist art from Romania in the first half of the 20th century.

Where and when did Constructivism begin?

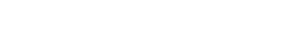

In 1915, Kazimir Malevich caused a commotion in the art scene in Moscow and later throughout Europe with his painting Black Square, which he exhibited in the corner of a gallery as though it were a Russian icon painting. Black Square had no subject matter other than an actual black square surrounded by a white border. Malevich opened up the possibilities of what could

be depicted in art, liberating it from the centuries old notion that art must reference the physical world. The suprematist forms of Malevich, such as the square, triangle, rectangle, and circle-the elemental geometric forms-signified a spiritual realm that humanity strove to reach, beyond what is visible in our daily lives. Thus, for Malevich, a simple square was not merely a square but a spiritual form that, though not tied to any particular religion, was meant to inspire deep contemplation and meditation in the viewer, without any superfluous details distracting the viewer’s eyes and mind.

Russian Constructivism

Malevich called his concept of geometric abstraction Suprematism, which then developed into Constructivism in 1919 in revolutionary Russia where idealistic artists became emboldened to merge art with life, producing textiles, advertising, architecture, photography, and film that featured Malevich’s abstract visual language. Artists began calling themselves “engineers” or “constructivists” to emphasize that the kind of art they were producing was useful in building a new, post-revolution society. However, by 1930, Stalin censored all arts, eliminating all Constructivism and forcing artists to adhere to the communist style of Socialist Realism.

International Constructivism

Constructivism continued to thrive outside of Russia, in many corners of Europe, from Romania and Poland to Germany and France, taking on the name International Constructivism. Artists like Hans Richter applied geometric forms in dynamic compositions to evoke depth and movement. They shared with their Russian counterparts an interest in modernization and industrialization, but unlike the art of the Russian Constructivists, their constructivist art was not political in the sense that they were it was not tied to a revolutionary ideology nor was it suppose to have a useful, socialist function. Constructivist art was a new, universal art that stood for the modern world and its technological advancement.

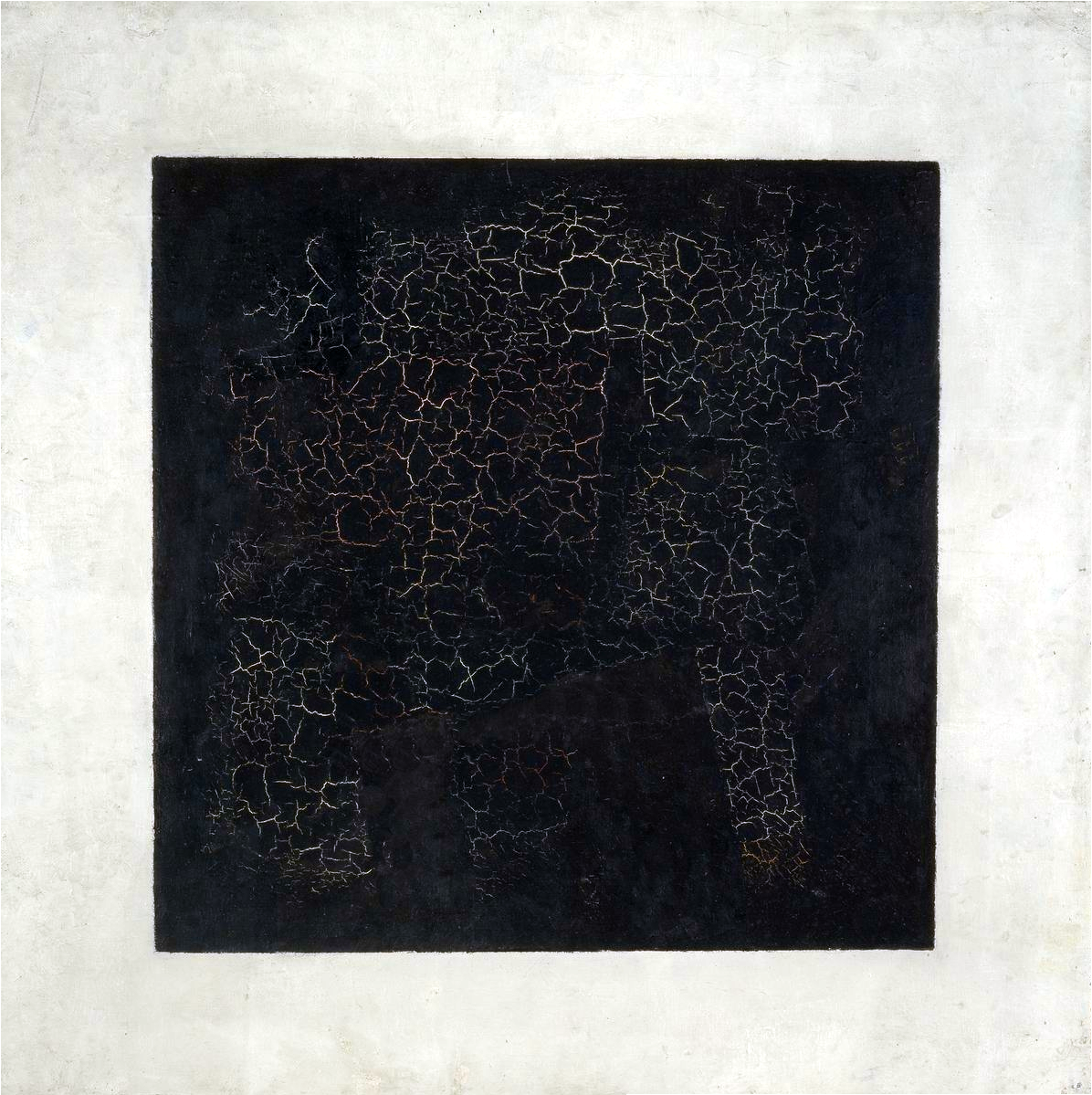

Hans Richter, Rhythmus 21, 1921

For example, in the German artist Hans Richter’s film “Rhythmus 21” from 1921, black and grey squares and rectangles dance with each other on a black background as they appear, disappear and overlap in one of the first abstract films ever created. See the entire film here. (from the Museum of Modern Art’s collection).

A Contemporary Take on Constructivism

Cyndy’s geometric paintings are closer to this international version of Constructivism outside of Russia, in which Constructivism’s spiritual and visual powers take center stage. Her painting Aspect of Light pairs abstract geometry with a landscape of clouds and electric poles that draw inspiration from Constructivism’s abstract language and its optimistic belief in the progress of modernity. Similarities exist between Richter’s film and Aspect of Light in the relations between the intersecting and adjacent squares and rectangles that give movement to the painting’s asymmetrical composition. There are differences as well. Cyndy’s painting, in addition to its colorful palette, is half grounded in reality and half grounded in abstraction and much more connected to nature than Richter’s film.

The coupling of Constructivism with motifs of nature is particularly evident in Cyndy’s painting Transmuting Presence (below). Two rectangles, of varying thickness, glide downwards across a dramatic sunset of deep and light blues, fiery reds, and calming yellows. The spiritualism that Malevich sought in his Black Square is on full display in Cyndy’s paintings, though the end results are entirely different.

Cyndy Carstens, Transmuting Presence

As a contemporary artist, Cyndy is not bound to the stringency of Constructivism, as practiced by Malevich and Richter, which dictates that artists must not employ any naturalistic subject matter. Rather, Cyndy reconfigures the geometric, constructivist elements in her skyscapes to give an otherwordly characteristic to the paintings while staying true to her painting style-of capturing nature’s harmonious and mysterious beauty through expressive brushstrokes and unique color combinations. Her coupling of the geometric with the organic is reminiscent of Marcel Iancu’s constructivist art. Iancu, a major Romanian artist who produced constructivist linocut prints for the Romanian art magazine Contimporanul (as seen on the magazine’s cover below, from 1924), altered constructivist art by introducing organic forms to his geometric compositions, such as the deformed ovals encroaching on the slanted architectonic object.

Romanian artists in the 1920s absorbed the constructivist style in their art but without completely copying it. They made it their own. Similarly today, contemporary artists like Cyndy are compelled to experiment with many styles in the history of art as they attempt to create their own visual language. Her geometric paintings are a testament to her talent and creativity and that of contemporary art overall, and to the important mark that Constructivism has left on the visual arts more than 100 years later.

Marcel Iancu’s print on the cover of Contimporanul magazine, 1924